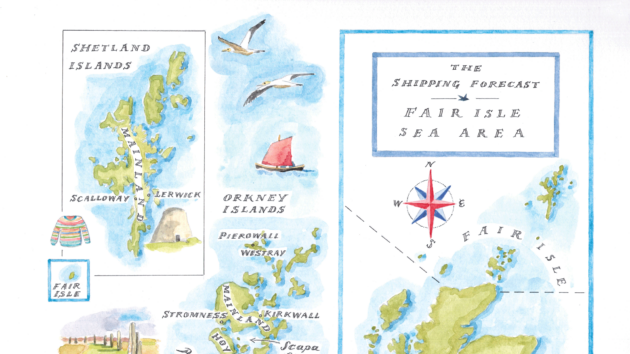

Celebrating 100 years of the BBC Shipping Forecast, Jane Russell takes us on a series of coastal cruises through the forecast sea areas, exploring some of the special places on offer in each of them.

The island of Fair Isle sits between Orkney and Shetland, and the eponymous sea area encompasses both of these island groups as well as the north coast of Scotland. These are certainly the most remote coastlines in the United Kingdom, with very changeable weather and big seas brought in by the train of Atlantic depressions.

However, although storms can occur, the summer winds are predominantly moderate southwest to northwest, with gales on average less than one day a month in June. Southeast to northeast winds are more common in spring and early summer and again in the autumn.

Drizzle is relatively persistent and fog is quite common – around eight days per month in June. But there are breaks with stunning blue skies, more so on the west side of the islands than the east.

The town of St Margaret’s Hope on South Ronaldsay. Photo: Ruth Craine / Alamy Stock Photo

Tidal flows are very strong and there are several places where the shape and type of seabed constricts or restricts them and creates breaking seas known locally as ‘roosts’. These roosts are a real danger to small craft, particularly in the Pentland Firth, especially with wind and swell against tide, when seas become violent and confused and break in multiple directions.

All of which sounds rather daunting, but the cruising benefits of the far north are the many hours of daylight and the chance to experience unspoilt nature in all its glory. Add to this a rich history of human settlement and activity that reaches back more than 5,000 years, and there are many good reasons to sail there.

Cruising around Fair Isle: E or SE 3 to 5, occasionally 6 later. Slight or moderate. Rain later. Good, occasionally moderate later

Our passage through Fair Isle began as we rounded Cape Wrath. It was blowing gently from the east and the sea was purring, not growling. Even so, there were periodic eruptions of spray from Duslic Rock and we kept well clear.

The beat was made much easier by the favourable current and by coffee time we were bearing away round the islands in the entrance to Loch Eriboll, the wind bending along the coast to follow us in.

Joanna Martin is an illustrator and printmaker based in County Down. Her designs are inspired by the sailing adventures she has around the island of Ireland and the West Coast of Scotland. Joanna’s love of maps with a coastal theme began with a series on Strangford Lough, where she and her husband Mark live and sail. Photo: Joanna Martin, Curlew Cottage Design

The scale of the loch feels monumental, with a massive ridge line to the southwest. The only indication of other human presence is the endless line of North Coast 500 campervans progressing like ants above the western shore.

With the forecast to come south of east we decided to anchor in Geodh an Sgadain, on the north side of Ard Neackie promontory. We considered going further down the loch to Camas an Duin but this nearer beach anchorage seemed appealing.

We sounded in between a couple of lobster pots and anchored in 3-4m near a pretty little fishing boat on a mooring. As we pirouetted in the whispers of breeze we could see the anchor below us and it looked well dug into sand.

Stromness proved to be a very attractive and stylish base for a few days. Photo: imagebroker.com / Alamy Stock Photo

The benefit of the long hours of northern daylight did not help us with what was to come because the promised southeast didn’t fill in until the last of the light at about 2330.

It arrived out of nowhere as a howling beast, much stronger than expected, funnelling down at us in ferocious accelerated gusts of 30 knots and more, and lashing us with rain. Within moments, we knew we were dragging. Very fast. No time for oilskins, just action stations.

I was at the helm and David on the bow, working our mechanical windlass to retrieve more than 30m of chain which was, by now, hanging vertically into the depths of the loch. The speed with which we came off the shelf was unnerving, not least because I knew that we had somehow cleared both the pot buoys and the reef extending northwards on the west side of the anchorage.

Anchoring in blackout

David managed to raise not just the anchor and chain, but an enormous ball of seaweed that we must have ripped through as we dragged. With the engine fighting hard against the gusts, our instinct was to try to re-anchor in the same bay. It was the closest possible shelter and everywhere else was unfamiliar.

I drove us back in to our earlier spot but just as the anchor was touching bottom another big gust took the bow off and we knew there was no chance. Now in complete darkness, there were no visual markers outside of the cockpit, no lights anywhere to guide us, and I had to trust the chartplotter much more completely than I usually would.

Photo: Mark Ellison / Alamy Stock Photo

Clear of the reef again, we motored hard up the loch in the blackout, the boat lurching as each fist of wind and rain smacked into us.

Mercifully quickly, we came out of the acceleration zone, and by the time we reached Camas an Duin the wind had bent round behind us again, but gently. We strained to catch a glimpse of the white house on the shore that was detailed in the pilot.

There were still no lights at all. With our searchlight we found our way inside the fish farm and clear of the moorings and at the second attempt re-anchored successfully. It took a while for the adrenaline to subside.

We had come through the situation OK, but it was a reminder of how quickly conditions can change and of how self-reliant we needed to be. In the morning we could see the full extent of this much more sheltered spot and we felt very foolish for not choosing it in the first place.

The passage to Orkney was smoother and faster than expected. Photo: Jane Russell

If the bad moments are payment for the good ones, we had earned a decent passage to Orkney. And so it proved to be. There was still enough south in the easterlies to give us more of a fetch than a beat, even cracking off a bit.

The only problem was that we had planned for more adverse wind and current and, despite reefing to slow down, we were arriving too soon. As we approached the Old Man of Hoy, the Scrabster ferry was passing and looked tiny in comparison to the lofty stone watchkeeper. With the wind now coming from SSE there was no roost at all and we decided to try cheating the tide by staying very close to the southern edge of the channel.

We did manage to cheat it, as the pilot suggested we might, but only with a lot of engine assist for a brief period where we had nearly 5 knots of current against us. Not to be recommended.

Article continues below…

Sailing the Shipping Forecast: The Hebrides

This is a spectacular but remote cruising ground. It is essential to be well-prepared and self-sufficient. The Hebrides sea area…

Sailing from Scotland to Ireland: ‘The mountains were swathed in a blanket of cloud and the waves became enormous’

The magic and mystery of the western isles of Scotland capture my imagination and draw me back every summer. This…

Taking shelter in stromness

Still slightly licking our wounds, we were very happy to be snug and safe on a pontoon berth in Stromness for the following few days while the wind blew strongly from the SE and then from the NW. And we weren’t the only visitors seeking shelter for a while, so it was a companionable time.

Several boats were heading west and a few were hoping to head north. We were now in the eighth week of our three-month round Britain adventure and, as the changeable weather continued, we knew that we didn’t have enough time to cruise Shetland as well as explore the east coast.

David, relieved to be round Duncansby Head and leaving the Pentland Firth behind. Photo: Jane Russell

If Orkney and Shetland are the cruising goal it is probably better to make them the focus and be poised ready to make the most of optimal conditions. The weather certainly wasn’t helping us to cruise around Orkney, but that didn’t mean we couldn’t explore.

Orkney buses and ferries would get us around. Skara Brae was top of our list. Older than Stonehenge, this UNESCO World Heritage site is Europe’s most complete Neolithic village. It overlooks the Bay of Skaill, which we gazed at rather wistfully as it seemed a perfect anchorage just then, but not, we knew, with the coming forecast.

On to the other Neolithic sites at Ring of Brodgar and Brodgar Ness, where we watched the excavations and marvelled at the ancient knowledge and skill that went into the dressing of the stone and the building of such structures.

The Still Room at Highland Park whisky

distillery, Orkney. Photo: Iain Sarjeant / Alamy Stock Photo

Kirkwall gave us the 12th-century cathedral of St Magnus. The lovely red and yellow sandstone building, now rather weathered in places, is the oldest cathedral in Scotland and underlines the age-old importance and sophistication of Orkney.

John Rae, the doctor and explorer who reported the fate of the Franklin expedition to the Northwest Passage, was born in Stromness and is buried in the cathedral cemetery. There is a further memorial to him near the altar. Kirkwall marina was looking rather bleak and windswept, but it would be a good place to stop during routes to the northern islands and to Fair Isle and Shetland.

Poignant wartime memories

A ferry to Lyness on Hoy took us to the Scapa Flow Museum, which charts the role of Orkney in both WW1 and WW2.

In better weather we would have picked up the visitor mooring there. The museum exhibits brought into perspective the tragic loss of so many lives in Scapa Flow. The ferry back to Mainland felt more poignant as we passed close to the invisible ships that remain sunken there as war graves.

Isle of Noss. Photo: Our Wild Life Photography / Alamy Stock Photo

We found a much happier story at the lovely Italian Chapel which was created by Italian prisoners of war who were building the Churchill submarine barriers. Led by an ingenious artist, a skilled group of prisoners turned two Nissen huts into a very special place of worship that, for them, felt more like home.

Stromness itself is a rather stylish small town of cobbled streets, vertiginous alleyways and houses fronting the water. It has its own excellent museum

as well as plenty of shops and places to eat. It was the perfect base for our wanderings.

But all good things come to an end and the northwesterly was moderating enough to give us some hope for a reasonable passage across the Pentland Firth.

Cyclonic, becoming NW, 4 to 6. Slight or moderate. Rain or showers. Good, occasionally poor

Having carefully studied all the advised timings and strategies, we ran down the east shore of Hoy to Cantick Head and continued south into the Firth, allowing ourselves to be set southwest at first to best meet the start of the favourable flow.

Outside St Magnus cathedral in Kirkwall

Even at neaps we could feel the complex currents tugging at us, first one way, then another. Despite all our planning, the turn of the tide was delayed on the predictions and our progress was conflicted and lumpy for longer than we had hoped. But turn it did, and we were soon squirted southeastwards towards and around Duncansby Head.

The Pentland Firth has a reputation for being the worst patch of water anywhere round Britain. With it behind us the water flattened out and we could relax and enjoy the Duncansby Stacks. We still had three knots of current and a moderate NW helping us southwards towards Wick and into the Cromarty forecast area.

Places to stop

On Orkney, most of the must-see places mentioned are on Mainland. Several key spots, including Skara Brae, are adjacent to anchorages or visitor moorings, but if the weather is not good, many are accessible from either Stromness or Kirkwall by bus. Likewise, there are ferries to the Scapa Flow Museum on Hoy.

From Pierowall, Westray Heritage Centre is the current home of the small sandstone neolithic figurine, known as the ‘Westray Wifie’, found at Links of Noltland (www.orkney.com).

A welcome to Shetland includes the motto ‘with laws shall land be built’ taken from the 1241 Law of Jutland. Photo: Europe / Alamy Stock Photo

On Shetland, the Shetland Museum and Archives in Lerwick has, amongst much more, a good display of clinker-built yoles. The Scalloway museum tells the story of the Shetland Bus – the famous WW2 operation transporting supplies and men between Norway and Shetland – also a good reason to anchor at Lunna under Lunna House. Jarlshof is a site of human settlement for more than 4,000 years including an Iron Age broch and Norse longhouse.

The Broch of Mousa, the tallest Iron Age roundhouse in Scotland is still standing and is home to breeding colonies of storm petrels. As in Orkney, most may be more accessible by bus or car if the weather is tricky. www.shetland.org

Everywhere, the midsummer celebrations are a good time to enjoy some local music.

Lerwick has plenty of maritime history. Photo: robertharding / Alamy Stock Photo

North Haven, Fair Isle

North Haven is a very useful stop between Orkney and Shetland and is the only good shelter on Fair Isle. Seals and birdlife abound and seem unperturbed by visiting humans. The quay is well protected but space is restricted and visiting boats frequently need to raft alongside each other (www.fairisle.org.uk).

Skara Brae neolithic village looks out over the Bay of Skaill. Photo: Our Wild Life Photography / Alamy Stock Photo

Shetland boats

Shetland boats originated in Scandinavia but were modified in a range of designs to suit the unique needs of the Shetlanders. Shetland yole rowing regattas and races run regularly throughout the summer and are fun to watch. Shetland Boat Week, in early August, celebrates the whole range of traditional vessels.

Exceptional malts

Lerwick distillery, where Shetland malt is made, and the Highland Park and Scapa distilleries in Orkney will all claim supremacy and locals will debate the topic with certainty. Surely the only way to decide is to try them, although the prices of some of their offerings are truly eye-watering.

The Scrabster ferry looking small under the towering gaze of the Old Man of Hoy

Out Stack

Out Stack, just northeast of Muckle Flugga, is the most northerly point of the UK and, as such, a rounding may be on your bucket list. In the right weather, it is probably a very good excuse to explore by boat some of the less visited places in Shetland.

Scottish Coastal Sailing: Getting around

Marinas and crew changes

NorthLink Ferries sail from Aberdeen to Kirkwall (Orkney) and Lerwick (Shetland), and from Scrabster to Stromness (Orkney): www.northlinkferries.co.uk.

Pentland Ferries run between Gills Bay and St Margaret’s Hope (Orkney): https://pentlandferries.co.uk.

Orkney Ferries (www.orkneyferries.co.uk) and Shetland Islands Council Ferries (www.shetland.gov.uk) connect within the island groups.

Geodh an Sgadain anchorage in Loch Eriboll looking innocent in the evening light. Photo: All images Jane Russell (unless stated otherwise)

Loganair flies to and between Orkney and Shetland from Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Glasgow and Inverness (www.loganair.co.uk) and within the island groups.

The Good Shepherd ferry and Airtask flights connect Shetland to Fair Isle (www.shetland.gov.uk).

There are marinas at Stromness and Kirkwall (both on Orkney Mainland) and Pierowall (Westray, Orkney).

There are also a number of well-located visitor moorings for vessels up to 18T throughout Orkney – more information about these is available through the marinas and on the Orkney Marinas website.

The Ring of Brodgar on Orkney dates back to around 2500BC

In Shetland there is pontoon berthing for visitors in the Small Boat Harbour in South Harbour, Lerwick. Elsewhere there may be a pontoon berth available in one of the many small boat marinas.

Many islands have piers or jetties that may be used but without restricting their use by ferries and other commercial vessels. Otherwise there are hundreds of anchorages. How lovely they are will be entirely dependent on weather conditions. Choose wisely and have back-up plans.

Pilotage information

A combination of Clyde Cruising Club’s Sailing Directions and Anchorages for Orkney and Shetland including North and Northeast Scotland and The Cruising Almanac (both published by Imray).

Also www.orkneymarinas.co.uk, which includes a very useful downloadable cruising guide, and www.lerwick-harbour.co.uk which has information for the 500 or so visiting yachts they host each year.

Enjoyed reading this?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price, so you can save money compared to buying single issues.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

-

-

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

-

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Note: We may earn a commission when you buy through links on our site, at no extra cost to you. This doesn’t affect our editorial independence.