Jason Beattie’s 1938 cutter Cumulus turns heads, but there are some costly realities that come with owning a beautiful piece of history

The motor launch headed towards us at speed across Chichester Harbour and then pulled up sharply alongside. ‘Can I just say,’ said a rather posh sounding man, ‘she’s a thing of rare beauty.’

A couple of days earlier we were sailing from our home port of Brighton towards the Solent when a yacht on the port tack began bearing down on us.

As the boat drew closer I bellowed ‘Starboard’ but to no avail. Presuming I was dealing with a novice, I gently veered away only for the other boat to readjust their course and head back towards me. I moved again and so did they. It was only when we were in spitting distance that I realised what was happening. The owner of the other yacht, sailing shorthanded, was on the deck taking photographs.

These are the delights of owning a classic boat. Naturally, I’m prejudiced but my yacht Cumulus, a 1938 cutter built by Williams & Parkinson in Conwy, north Wales, is a thing of beauty, especially when she has all three tan sails up as was the case when she attracted the attention of my photographer friend.

Call me a fool (I prefer the word romantic) but I bought a wooden boat with my eyes open. I knew they have a tendency to leak, that the maintenance is far more time-consuming than with a plastic boat, that the upkeep is more expensive and that there is a greater likelihood that things will break, fall apart and generally go wrong.

All of this was apparent from a very early age when my parents in their wisdom decided they would like to spend their summers cruising on a 26ft wooden yacht with two small children. My holidays were spent in a cramped pipe cot, being sick in buckets and driving my mum and dad to despair by falling overboard rather too often.

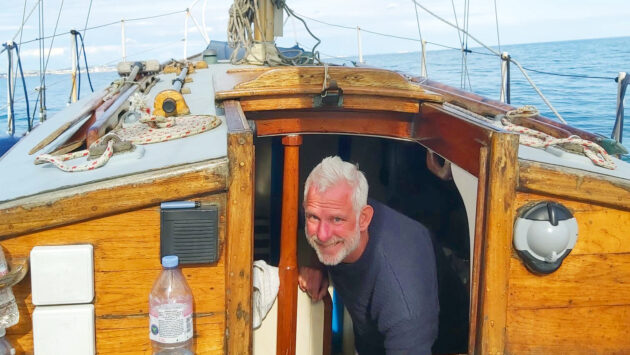

National newspaper journalist Jason Beattie takes the helm of Cumulus, a 1938 cutter built by Williams & Parkinson in Conwy, north Wales

Endless varnish

I witnessed first-hand all the perils, pitfalls and imperfections of owning a wooden boat, whether it was constant drips from the leaks over my bunk, the bitter winters spent scrubbing down and repainting the hull or the endless amount of varnishing. Somehow this experience didn’t act as a deterrent.

The dream was always to buy a boat of my own but work, small children or money (lack of) kept getting in the way.

I still read magazines about boats (including YM, naturally), I still cadged day sails with friends, I still pottered around in dinghies on the Helford and I still spent more hours than is probably healthy looking at the many yachts for sale on the internet.

In fact I did everything except for actually buying a boat. Then one day I was scrolling though yet another website and there was Cumulus. ‘That’s the one,’ I said to my wife.

It is difficult to articulate exactly why Cumulus was exactly the one. When you identify ‘the boat’ it is the bringing together of memories, aspiration, romance, seamanship and, more prosaically, the condition of your bank balance.

Article continues below…

‘Our dinghy outboard was being smashed to pieces by the swell’

Our dinghy is the equivalent of everyone’s car at home; it’s how we get from our boat at anchor, to…

‘I spent hours in the water in hurricane conditions’

When we saw the race briefing it was a little bit fuzzy,’ John Quinn told me, recalling events that had…

Her lines, to my eye, were wonderful. The design has a hint of Hillyard which evoked the nine-tonner my godfather used to sail. The bowsprit, which I knew I would curse every time it cost me a few extra quid in mooring fees, added a touch of grace. Inside, she had the comfort you associate with a traditional gentleman’s yacht. I also knew I was buying a piece of history.

One of the delights of having Cumulus is I know the names of all the previous owners, from the Welsh doctor who commissioned her from new, to Ollie, who reluctantly sold her to me as he had reached the age where he would rather live permanently in a house. On dry land.

With the boat came many, though not all, of the previous owners’ logbooks. On idle days I can read how Cumulus sailed to France, the Netherlands and the Baltic.

My view is that I have not so much bought Cumulus, but borrowed her so I can look after her until the next owner comes along. My only goal, apart from spending a few weeks a year cruising, was to hand her on in better condition than when she came into my possession.

Without wanting to sound too pompous, I wanted to preserve this small but elegant piece of craftsmanship and maritime history. It was at this point the reality struck.

The beautiful lines of Cumulus, a 1938 cutter built by Williams & Parkinson in Conwy

Over the side

All boats are expensive but wooden boats can be eye-wateringly expensive. The priority the first year was to get the engine and the electrics sorted. The next year my wife insisted on a furling jenny after watching me lean over the pulpit in a Force 6 trying to unhank the sail and quickly concluded that the cost of a new sail was probably preferable to losing me over the side.

Then the sheaves jammed at the top of the mast so that required some re-rigging. There was a stretch of rotten wood on the gunwale which needed replacing. Did I mention that we found diesel bug in the tank? Or that the navigation lights were broken? And there’s a mystery leak which I still have not been able to trace?

Pretty soon I had already spent more on the upkeep of Cumulus than I had on the original purchase.

And I don’t begrudge a single penny.

She sails beautifully with the wind on the beam, easily chalking up seven knots. She’s less elegant heading into the wind but that was to be expected. The deep cockpit is far more secure than those of most modern boats and surprisingly dry. Weighing just over eight and a half tons, she more than holds her own in rough seas.

We’ve sailed down to the West Country and across the Channel and pottered happily around the Solent. Remarkably, given she draws almost six feet, we’ve only gone aground a couple of times. Well, maybe more than a couple…

Jason Beattie spent his childhood summers dinghy sailing and cruising

Inside, she sleeps five at a push with a generous vee-berth in the forecabin and a double bunk and a galley bunk in the main cabin. The grabrails are well positioned, the seating comfortable and, as long as you are under six feet tall, you can stand up (a luxury not always available on older boats).

Admittedly, the facilities are somewhat basic compared with modern yachts but they cannot compete with the atmosphere which comes with an oil lamp-lit wooden cabin.

We were once moored up alongside an X-yacht and her owner looked on, amazed as I sat in the cockpit refilling the lamps with oil. ‘What is that?’ they asked, as though they had just walked into a museum.

On comparing notes, they also discovered that Cumulus did not have a washing machine, nor two showers or a fridge either.

If there is a downside it is the lack of manoeuvrability. By far the most fear-inducing moments of any voyage are the leaving and arriving at harbours.

Stubborn refusal

Deep-keeled boats and cramped marinas are rarely a perfect match. Cumulus has more of a turning arc than a turning circle and stubbornly refuses to go backwards in a straight line so it is always a challenge entering tight berths. I look on with envy at yachts with bow thrusters that can spin on a penny.

Having said that, most harbour or berthing masters are very accommodating if you radio in advance and explain your limitations.

Associations such as the Old Gaffers Association enjoy lively calendars and plenty of opportunity for owners to meet

This summer we visited St Valery-en-Caux in Normandy and as we passed through the lock I shouted in my best French ‘jetée facile s’il vous plait’ at the harbourmaster and he kindly obliged with an end-of-pontoon berth. Harbours along the south coast of England have been equally obliging.

Perhaps the greatest joy has been getting to know the boat. The more hours I spend on the water the more I am learning about her foibles and capabilities. I’m better at judging how much sail she likes and how much she dislikes being close to the wind.

I’ve also learned that you are always learning. Despite being brought up on boats it was only when I bought my own did I appreciate the gaps in my knowledge. Already I am a better sailor, passage planner and navigator.

My varnishing has improved – I can bore people for hours about the use of thinners, the right sanding paper and the optimum number of layers. Though I’m still making lots of schoolboy errors.

My first sail through the Solent saw us go backwards after I misread the tidal stream. This winter I decided to paint a green strake along the waterline but failed to use antifouling so the boat now has an unsightly skirt of weed around her sides.

Jason Beattie looks out from below

I’m constantly grateful to the camaraderie of fellow boat owners who have leant me tools, advised on wood preservation and provided tips on where to purchase those items peculiar to older vessels such as wicks for the oil lamps and porthole seals. Cumulus is not only ‘the one’ – she’s the one for life.

In one of the log entries of a previous owner from 1971 there’s a tersely-written entry. It reads: ‘Off Dover. Force 10. I’m terrified. Boat fine.’

I’d have been terrified too but I can confirm Cumulus is fine. Indeed, she’s a thing of rare beauty.

Lessons learned

A Survey is essential – You should get a survey before you purchase any boat but that rule especially applies with a wooden yacht. Inevitably, the older the boat the more likely there are to be problems. I used a surveyor who specialises in wooden boats and was grateful to find Cumulus was in pretty good nick overall. If there had been major structural damage I would have been prepared to walk away from the deal.

Buy shares in a varnish manufacturer – There is no escaping that a wooden boat requires a lot of upkeep. In my case, as someone who spends their working life in front of a computer, there is a pleasure to be found in using your hands. Only commit to owning a wooden vessel if you are sure you have enough time to do the maintenance. There is no quick way to apply varnish.

Don’t be a purist – I am grateful that Cumulus came with a metal mast and boom. Yes, wooden spars would be more aesthetically pleasing but they really add to the already considerable workload. Cumulus may be a piece of history but there’s no need to be stuck in the past. My first purchase was a furling jenny after my wife witnessed me leaning over the pulpit in a Force 6 trying to unhank the sail and concluded the traditional ways were too hair-raising.

Mirror, signal, manoeuvre – Think carefully about where you are going to keep the boat. Long, deep-keeled yachts are about as easy and graceful to manoeuvre as a rhinoceros on a skateboard. Many modern marinas are designed for boats with sharp turning circles and bow thrusters, not cantankerous old yachts that refuse to go backwards in a straight line. That said, harbourmasters will usually go out of their way to find you an accessible berth if you alert them in advance.

Enjoyed reading this?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price, so you can save money compared to buying single issues.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

-

-

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

-

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Note: We may earn a commission when you buy through links on our site, at no extra cost to you. This doesn’t affect our editorial independence.