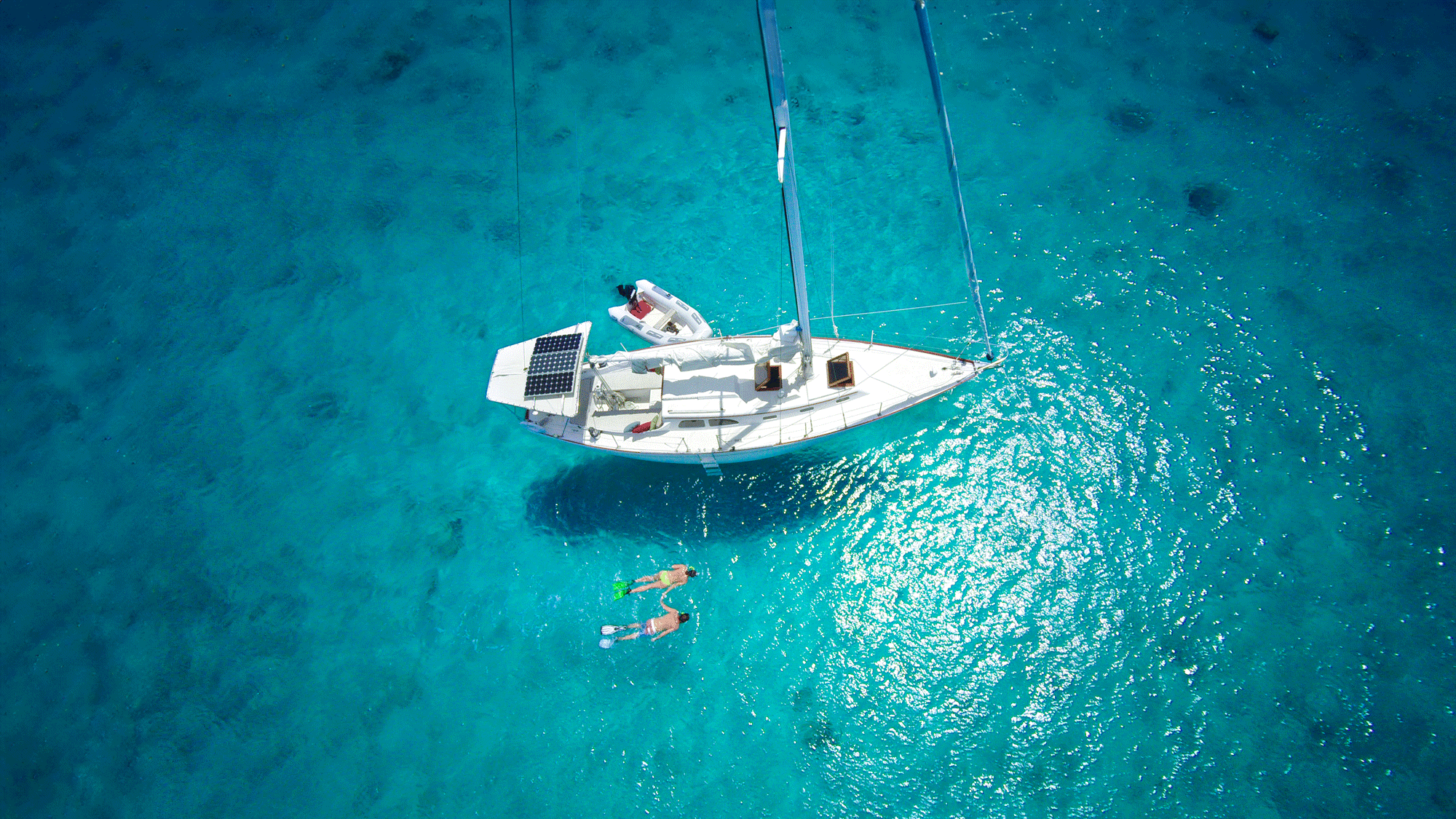

Some boats need persuasion to make to windward, so tweaking the sails to best advantage can make all the difference. David Harding offers a few tips

Who doesn’t just love heeling over, bouncing up and down, getting cold and wet and pointing in a direction that bears little relation to where you want to go?

Given that beating is not the most relaxing point of sailing, it makes sense to sail the boat upwind as efficiently as possible. That way you’ll not only get wherever you’re going sooner, but you will also have a more comfortable time because greater efficiency means less heel and weather helm. If you’re enjoying yourself, or in danger of arriving too soon, you can always slow down. It’s much easier to slow down because you want to than to speed up because you have to.

A little sail tweaking can even make the difference between getting there and not getting there, as Ron Salinger found when we arranged to meet in Poole Bay for a photo session with his Gib’Sea 242.

Ron set off from Christchurch against 15 knots of westerly wind. His previous boat, a 5.8m (19ft) Prelude, would have swallowed the miles with ease. She might not have kept the crew completely dry, and the waves would have felt bigger than on the Gib’Sea, but she’d have got there in good time. With the Gib’Sea, however, it was a different story: she refused to make to windward. So, instead of heading west, Ron stayed in Christchurch Bay and I headed east to meet him.

Whys and wherefores

Much of the Gib’Sea’s reluctance was due to her underwater configuration. For a start, her flat centreplate generates little lift compared with a keel – fixed or lifting – that’s properly profiled. It just doesn’t work as well. Another hindrance is the outboard. Too big to lift out of its well and store in a locker, it can’t be tilted up for sailing either, so the three blades of the prop combine with the drag of the aperture in the hull to act as a very efficient handbrake.

Article continues below…

How to sail sustainably: ‘The Atlantic taught me how to calculate a boat’s carbon footprint’

For nearly three decades, I have been deeply involved in shaping environmental solutions across many industries, from agriculture to aviation.…

How to get the best from your sailing boat: Learning how to ‘change gears’

Many of you, like me, probably started their sailing adventures in small dinghies. The purity of just you, the wind…

Compromises

With these compromises to overcome, the Gib’Sea needs some encouraging. Plenty of other 7.3m (24ft) cruising boats would oblige by still making upwind if trimmed and sailed as Ron’s Gib’Sea was. The difference is that, with this boat, there’s simply less tolerance.

Get it right and she goes. Get it slightly wrong and she doesn’t.

We learned little on the first of our two outings because the wind refused to play. Second time out, however, we had 12 knots building to around 15 – perfect conditions for sail-tweaking.

I asked Ron to start by sailing as he normally would, so I could observe the settings before making any adjustments.

How we started

Initially, Ron chose full mainsail and about four rolls in the headsail. Feeling the boat was overpowered, he took a slab in the main and let out a little more headsail to balance it.

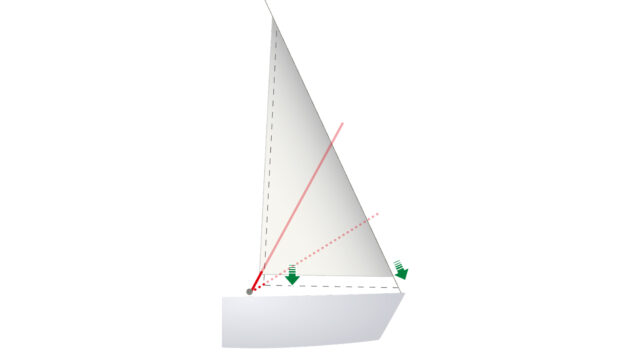

The mainsail trim problem

Here the topping lift hasn’t been released, so the boom cannot tension the leech (an oversight in this instance, but commonly seen). The sail is also too full, contributing to excessive heeling force and too little lift.

With the mainsheet car to windward, the boom is close to the centreline and the boat is heeling too much – just look at the angle of the tiller necessary to counter the weather helm.

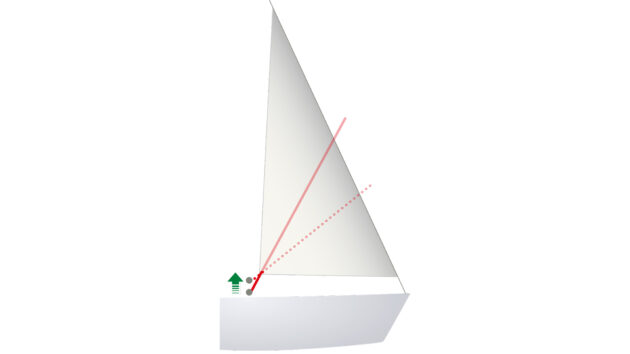

The mainsail trim fix

To show what could be done without reefing the mainsail, we flattened it using all the tension we could get on the backstay and outhaul, along with more halyard and sheet tension. We also dropped the car down the track.

When a boat becomes over-powered and starts to heel too far, it helps to drop the car down the track. If there’s no track, keep the kicker tight and ease the mainsheet.

Because the boat was still over-powered and highly sensitive to carrying too much sail, we reefed the mainsail. Plenty of foot, luff and leech tension ensure a nice shape.

It’s vital that the leech pennant pulls the clew both aft and down to ensure a tight foot. This one is slightly improvised, but it works.

Headsail trim

In an easterly breeze of 14-16 knots, our initial setup saw us sailing a course of around 135° at 2.8-3.2 knots and with a heavy helm.

Occasionally we would sail slightly lower, to 140°, at 4.5 knots. After our tweaks, and with no shift in the wind, we gained a full 10° of pointing, to 125°, while maintaining 4.7 knots, and could squeeze a little more height at the expense of some speed.

While it’s hard to be precise with numbers, there’s no doubt that the changes had an appreciable effect, not only on speed and pointing (our tacking angle came down to a respectable 90°) but also on balance and in reducing leeway.

Leeway is a significant factor, of which a compass course takes no account. If a boat drops below a critical speed in relation to the wind, leeway tends to increase dramatically. The Gib’Sea is vulnerable in this respect because of her flat centreplate.

The headsail trim problem

The major issue here is undersheeting: the headsail is too full and much of it is producing no drive.

The headsail trim fix

Sheeting the headsail in harder greatly improved its set and the balance of the boat, helping counter the weather helm. We left the car at the aft end of the track.

Full headsail

As the wind moderated later on, we needed more sail to keep the boat powered up. In just a couple of knots less wind she felt sluggish, clearly being as sensitive to too little sail as to too much, so we shook out the reef in the main and unrolled the rest of the headsail.

This revealed a problem I had noted on our first outing in very light conditions: that the sheeting point was too far forward or, looked at another way, that the sail was too long and/or high in the clew. That meant the leech was too tight and the foot too loose, creating an inefficient shape that increased heel and reduced speed.

Lowering the tack of the headsail will lower the clew and effectively move the sheet lead aft

As a good starting point, a continuation of the line of the headsail’s sheet should meet the luff at mid-height. Any higher means the car needs to be moved aft: lower that it should go forward. However, raising and lowering the tack and/or sheet lead can have a similar effect, as illustrated below.

Raising the foot block as a temporary measure has the same effect

Top tips for headsail trim

By observing how a boat’s performance relates to the sail shape you will soon come to recognise what’s right and what’s not. We haven’t mentioned telltales in this feature, but the rule of thumb is to have them all flying horizontally on both sides of the sail.

In the looking-up-the-sail ‘after’ photo, the top windward telltale is flying closer to vertical than horizontal. This is normal and desirable when a sail is being used towards the upper end of its wind range. It indicates that the top is more open, or twisted, which will help keep the boat on its feet.

The full headsail trim problem

This is a good angle from which to study a sail. The leech is very close to the spreaders and to the back of the mainsail. In the jargon, the ‘slot’ (between headsail and mainsail) is too closed, or there’s too little twist.

As a guide, the foot of the headsail should be close to the shrouds as the leech approaches the spreaders. That’s clearly not the case here. It looks all wrong.

The full headsail trim fix

This was a major part of the problem: the tack was raised above the drum on a shackle and a strop.

The first step was to remove the shackle and bring the tack down as close as possible to the drum.

There’s no scope to move the car further aft on the track to tighten the foot and open the leech.

Moving the sheeting position aft by running the sheet through an extra block attached to the foot-block. Don’t let the sail flog though!

The view from below clearly shows the more open ‘slot’ between the headsail and mainsail. One effect is less back-winding in the mainsail.

The foot is closer inboard, the leech is further from the spreaders, the shape looks better and the boat is heeling less, pointing higher and going faster with a lighter helm.

Conclusion

Eking and tweaking

Boats with underwater configurations like the centreplate version of the Gib’Sea 242 present challenges when it comes to upwind sailing. To make respectable progress they need to be sailed with a higher degree of precision than many other boats. The good news is that the challenges can be overcome to a large extent and that the same sail-trim principles apply almost universally – so if you can get a boat like this going, you should find anything else a doddle. It can help make you a better sailor.

Enjoyed reading this?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price, so you can save money compared to buying single issues.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

-

-

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

-

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Note: We may earn a commission when you buy through links on our site, at no extra cost to you. This doesn’t affect our editorial independence.